Set Up Google Scholar to Find Class Readings on Your Syllabus

Let me start with an only slightly edited e-mail exchange with a student during a class I taught.

Dr. Miller,

None of the class has been able to locate any of the assigned readings or work so far. I emailed my classmates last week assuming that I was the only one that couldn’t find anything, but evidently none of us know where any of the readings are.

For those unaware, I’m a big proponent of relying on journal articles to teach undergraduate classes for multiple reasons. One, a field like mine—peace science within the subdiscipline of international relations—is conspicuous as an article-driven research program. Most scholarship first appears as a peer-reviewed article before the author/authors amend and update the article with other related projects into a book. Students are already paying for the library’s subscription services as part of their tuition; so there’s no added cost, beyond optional printing fees, to obtain a relevant course reading on one of my syllabi. Second, textbook markup is outrageous. I try to do what I can to help students avoid paying any more than they must for a university education.

My syllabi say to obtain the course readings from the university library through its various journal subscription services (e.g., JSTOR, Blackwell-synergy). I build in an assumption that students have learned somewhere along the way about how to use the library for class readings or research papers in their classes. I remember that was one of the first things Ohio State taught me when I arrived as an undergrad for orientation and that was in 2002.

I got this email in response after telling this student (and the rest of the class) about how to use the library to find the readings.

I’m a senior here and I’ve never seen or had a professor use the library website before, so I’ve done literally none of the readings, and again several of my classmates haven’t either. The midterm is in four days, correct? I’ll try to get them all done by then, otherwise I might have to withdraw or something.

Oof. So, yeah. Apparently a large number of students in my major at my institution are not learning how to do this. Let me make it easier for my students by providing a guide on how to use Google Scholar to speak to the university’s library and retrieve journal articles with the easy-to-use interface that led us to fall in love with Google in the first place. What follows is intended for my students but is generalizable for professors at other institutions.

Set Up Google Scholar

First, go to Google Scholar. You’ll see this page.

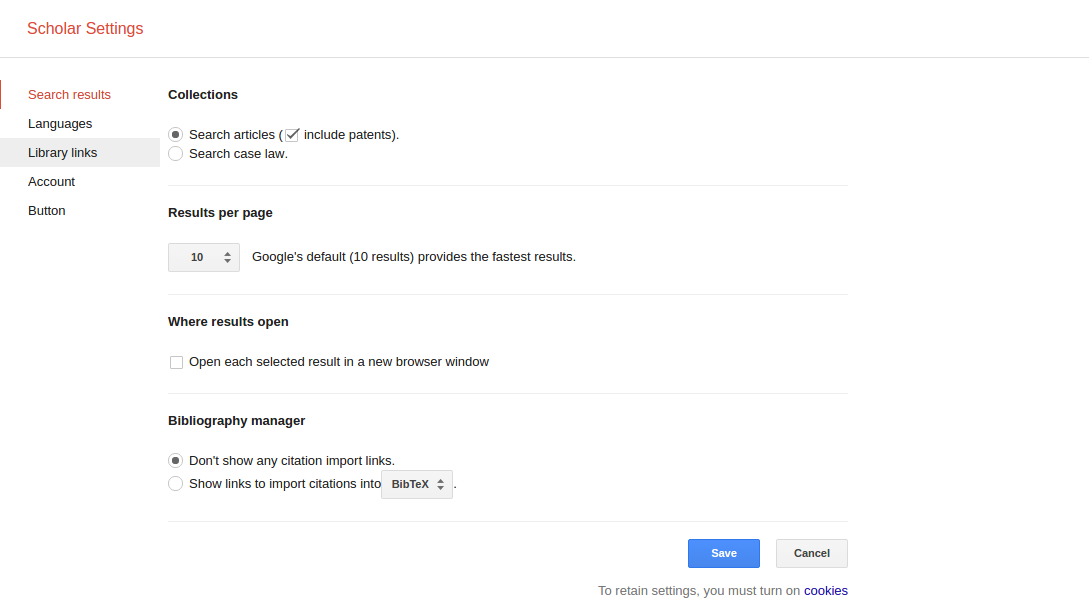

Do you see that link near the top right that says “Settings?” Click that. You’ll get here.

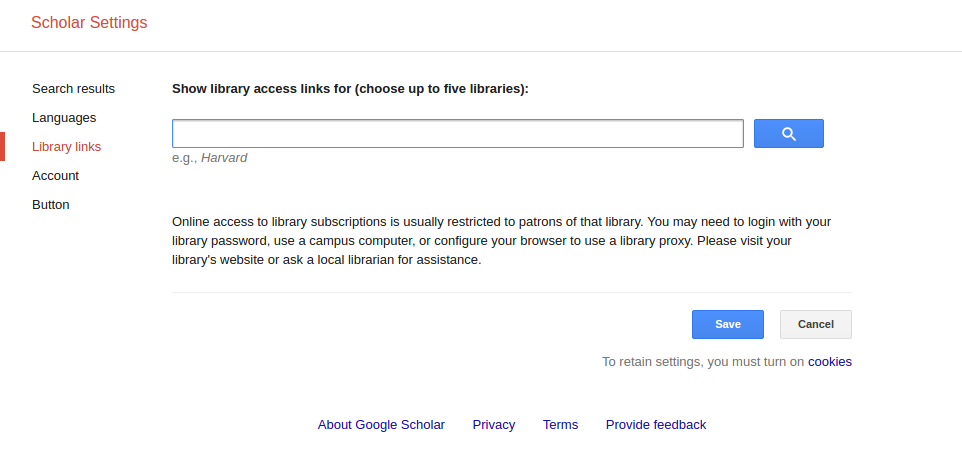

See that link on the left, helpfully shaded in the screen capture, that says “Library links?” Click that. You’ll arrive here.

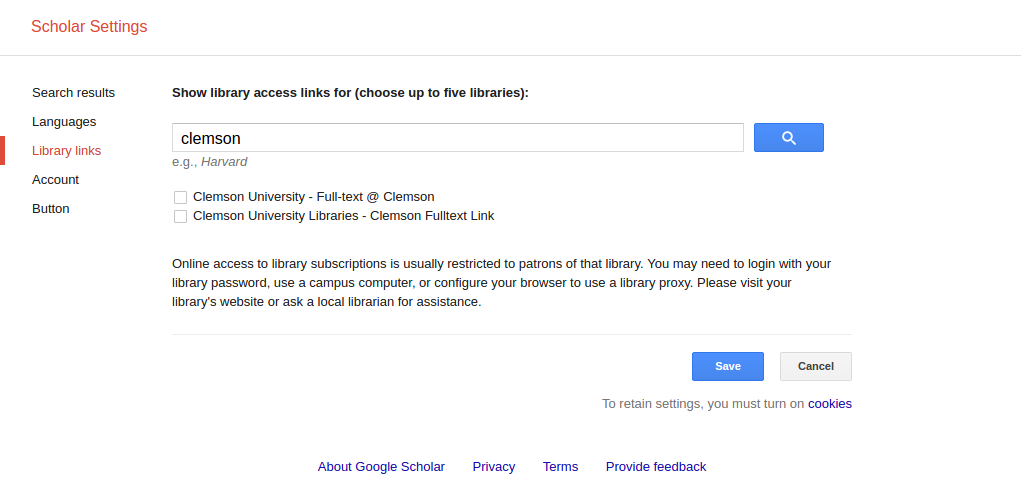

Once you’re here, enter the university you attend. Do note Google Scholar can speak to just about any library in the world. Enter your university—we’ll enter “Clemson”—and click the magnifying glass icon next to the search field. You’ll get something like this.

See those check boxes next to the Clemson links? Select both and press that blue “Save” button. Once you do, you’ll be returned to Google Scholar’s main page. You can begin searching for journal articles that appear on your syllabus.

Let’s start with the benefit of Google Scholar for finding your class readings in two scenarios. In the first, the library has access to the journal and the article, but the library’s search engine is not as sophisticated or flexible as Google’s search engine. In the second scenario, the library does not have access to the article, but Google Scholar can find you a copy anyway.

Google Is Better Than Your Library’s Search Engine

I’ll use the case of this Sarkees, Wayman, and Singer (2003) article that I routinely assign in my upper-division international conflict course as an illustration of the first scenario. I like this article for multiple reasons. Simply, it’s a data piece that introduces the Correlates of War war data in an easily obtainable journal article before the authors later extended this project into a book. The article does well to introduce my students to what war is, what are different types of wars, and what we can say about the distribution of different types of war and war’s characteristics over time.

We’ll start by looking for this article with its main title—“Inter-State, Intra-State, and Extra-State Wars”—on Clemson’s library website. When we enter that search term in quotes, we’ll get this result.

This is a peculiar result because we simply entered the main title of the article in quotes and Clemson’s library couldn’t find an article to which it has access.1 If you were to enter the exact same search term into Google Scholar, the result would identify exactly what you wanted.

I want the student to see two things in the above screengrab. First, the “Full-text @ Clemson” link would direct you to Clemson’s library, prompting you to elect which subscription service you want that has access to this article (i.e. JSTOR, Academic Search Complete, or Oxford Journals in this example). Select “Article” for any one of those and you will be prompted to log into the library with your Clemson username and password. Do that and you’ll get your article.

Alternatively, Google is adroit at crawling through university websites to locate articles as PDFs that some professor may have left on her/his university website for posterity. It’s not uncommon for professors to make their own published work freely available on their university website to anyone who wants it. In this case, it found a copy at the University of Michigan. This feature of Google Scholar will be useful for the next scenario.

Google Scholar May Find Something Your Library Can’t Find or Doesn’t Have

Google Scholar may be useful when you’re looking for an obscure article, or an older article, that your library may not have digitized. Again, not every university has a library like Harvard or Stanford and not every university may be (understandably) willing to pay the exorbitant price that journals and electronic storage facilities charge for access. Even Harvard University, the richest university in the world, is balking at these costs.

Consider the case of the Jones, Bremer, and Singer (1996) article that I also routinely assign in my upper-division international conflict course. This is another data piece I like to assign because I want students to understand what do we mean with terms like “war” and “militarized interstate dispute.” This article introduced what we know now as version 2 of the Correlates of War (CoW) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data set and gets my students to more clearly understand the concepts we use and how we operationalize them. It’s almost required reading at the grad level in international conflict as well. Basically, everyone in my field who works with that data has read this article and obtained a copy of it somewhere in their travels.

However, this article is now over twenty-years-old. Conflict Management and Peace Science, one of my favorite journals in the field, appears to be among a subset of peace science journals for which older articles are not readily accessible.2 For the sake of Clemson students, the university’s library only has all issues of Conflict Management and Peace Science from 1999 to the present. That would exclude the Jones, Bremer, and Singer (1996) article that might otherwise be the most widely cited article in the journal’s history.

No matter, Google Scholar will find a copy for you.

Notice that we can thank a team of researchers at Stanford University for making a copy of this article freely available. Additionally, a normal Google search will also find that the Correlates of War project made a version freely available on its website too.

TL;DR

Google Scholar is your friend. Use it for finding journal articles for your undergrad papers and for professors who are trying to save you some money by avoiding the use of textbooks in the class. I used to mention Google Scholar in my classes but I’ll make sure students read this in the first week instead.

-

To be fair, if you were to enter the article title without quotes, the library would find it as the first result. ↩

-

I encountered a similar situation in grad school at the University of Alabama looking for this Raymond (1996) article in International Interactions. It turned out to be the basis for what became my first publication, but Alabama’s library did not have an electronic version of this article. I got lucky because the library had a physical copy instead. ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.