A (Partial) Analysis of RuPaul's Lip Sync Songs from RuPaul's Drag Race

I’m in the gradual process of rehauling my {dragracer} package to make it more feature-rich for interested users. As far as R packages go, it was never going to be something super useful or in high demand, like {dplyr} or {devtools}. However, I want it to be more than it currently is because I could see it possibly being something useful, like {palmerpenguins} and especially {starwarsdb}. Down the road, I want to get a cheap publication in something like a Journal of Open Source Software for this. However, such a publication would require the package being much more than it currently is. It could get there, but it’s not there now.

One new addition to this R package is a comprehensive list of songs that have appeared as lip sync songs on the show across all its seasons. This data set is in active development and you can see a pilot version of it on Github here. To make these data something you could actually use, I’m (slowly) adding information from Spotify about all the songs that have appeared as songs to which contestants have lip-synced. Such a data collection process is tedious, especially as it pertains to using Spotify’s API. However, it does point to something that a user could do with these data (once they’ve been fully assembled).

Here, I’ll point to such a potential use of these data, leveraging {spotifyr} in R along with some pilot data in {dragracer}. I’ll have to defer to {spotifyr}’s documentation for more, and obviously point an interested user to Spotify itself for getting set up with a developer account.

First, let’s declare the R libraries’ I’ll be using in this post.

library(tidyverse) # for most things

library(stevemisc) # for graph formatting

library(kableExtra) # for tables

library(spotifyr) # for use of Spotify

Next, let’s get a sense of the pilot data I’ve assembled. These are all songs for which RuPaul was primary artist/performer that were featured as a song for which there was a competitive lip sync. More often than not, these competitive lip syncs were a “Lip Sync for Your Life” or a “Lip Sync for the Crown.” RuPaul often strategically times these songs to appear on her show as they coincide with album releases proximate to that season. “Cover Girl (Put the Bass in Your Walk)”, perhaps best known as RuPaul’s runway song on the show, also appeared as the “Lip Sync for the Crown” of Season 1 and was the first “Lip Sync for Your Life” of Season 2. Two of these tracks are not tracks that appear on a RuPaul album, but are instead remixes that appear on a different album.

readxl::read_excel("~/Dropbox/projects/dragracer/data-raw/manual/songs.xlsx", sheet = 2) %>%

filter(artist1 == "RuPaul") -> rupaul_songs

rupaul_songs %>%

select(-artist1) %>%

kbl(., caption = "A List of All Songs by RuPaul that Appeared as Competitive Lip Sync Songs in RuPaul's Drag Race",

format="html",

table.attr='id="stevetable"',

align = c("cclll")) %>%

column_spec(5, monospace = TRUE)

| season | episode | song | remix | spotify_id |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s01 | 1 | Supermodel | 36Rpz4MZQhGknLEmTmHr8v | |

| s01 | 8 | Cover Girl (Put the Bass in Your Walk) | 7jman10UPhzhtOOqZLjSsh | |

| s02 | 1 | Cover Girl (Put the Bass in Your Walk) | 7jman10UPhzhtOOqZLjSsh | |

| s02 | 11 | Jealous of My Boogie | Gomi & RasJek Edit | 0PsfIPOuOuYfyt3JAoK8Po |

| s03 | 15 | Champion | DJ BunJoe’s Olympic Mix | 4OqiUe0PIAYoEj3cWTNRnJ |

| s04 | 13 | Glamazon | 5CWWW4y4Px1dZcLwgzsgoD | |

| s05 | 12 | The Beginning | 10Xt9nkxQZNsPDtg30xpvR | |

| s06 | 12 | Sissy That Walk | 5PHPENfE3RVmHGAA2A7Hfx | |

| s07 | 1 | Geronimo | 1w6DRfEwDvMYaNRRCn3MiC | |

| s07 | 12 | Born Naked | 20GNVIllZWk2vF8p6Cz7uP | |

| s08 | 9 | The Realness | 1oSUTFfnEwftOTRxpLKWOY | |

| s09 | 12 | U Wear It Well | 60WR7ZzcpMx0Q5A0zoQsyM | |

| s10 | 12 | Call Me Mother | 5LCKQ7PXZRIKnBbABb7ed0 | |

| s12 | 14 | Bring Back My Girls | 7IM8lvafzONUM3aV6NZogU |

Notice that all these tracks have unique 22-character identifiers on Spotify. Here’s where I’ll admit I don’t really use a streaming service for music, like a Spotify, and I can’t tell immediately if these are identifiers unique to the song or unique to a particular user’s upload of the song. No matter, the way we’ll be using these identifiers will somewhat gloss over this issue. Let’s grab those unique identifiers for RuPaul’s songs (and appropriate remixes of them).

rupaul_songs %>% distinct(spotify_id) %>% pull() -> rupaul_ids

Next, let’s start using {spotifyr} to learn more about these tracks. Of note: you’ll need a developer account with Spotify and will need to declare a client ID and client “secret” ID as environmental variables in R (i.e. in .Renviron). Once you’re set up with Spotify, you can do any number of things in R with Spotify data. Here, I’m going to keep it simple and extract audio feature information for all these tracks on Spotify using the get_track_audio_features() function in {spotifyr}. Then, I’m going to merge in the information from the rupaul_songs table for ease of identification.

rupaul_features <- get_track_audio_features(rupaul_ids)

rupaul_features %>%

# left join in, on `id` (or `spotify_id`)

left_join(., rupaul_songs %>% select(spotify_id, song, remix), by=c("id"="spotify_id")) %>%

# group-by slice because Cover Girl appears twice.

group_by(id) %>% slice(1) %>% ungroup() -> rupaul_features

Do that, and you’ll get a table like this full of information. Here’s a snapshot of it.

rupaul_features %>%

select(song, remix, danceability:tempo, duration_ms:time_signature)

#> # A tibble: 13 × 15

#> song remix danceability energy key loudness mode speechiness acousticness

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 Jeal… Gomi… 0.71 0.721 2 -7.77 0 0.0449 0.0876

#> 2 The … <NA> 0.586 0.809 0 -4.98 0 0.0525 0.000121

#> 3 The … <NA> 0.708 0.814 7 -5.74 0 0.045 0.00219

#> 4 Gero… <NA> 0.88 0.928 6 -6.34 1 0.233 0.0107

#> 5 Born… <NA> 0.634 0.86 4 -3.55 1 0.206 0.0207

#> 6 Supe… <NA> 0.792 0.562 7 -11.4 1 0.0929 0.0152

#> 7 Cham… DJ B… 0.706 0.83 1 -5.15 0 0.0469 0.00481

#> 8 Glam… <NA> 0.805 0.595 9 -4.78 0 0.0457 0.00214

#> 9 Call… <NA> 0.859 0.828 6 -6.92 0 0.0529 0.0156

#> 10 Siss… <NA> 0.826 0.614 11 -4.22 1 0.0561 0.0191

#> 11 U We… <NA> 0.775 0.942 1 -5.44 1 0.0615 0.0284

#> 12 Brin… <NA> 0.913 0.729 6 -7.96 0 0.0515 0.0108

#> 13 Cove… <NA> 0.918 0.746 6 -4.78 0 0.0851 0.00334

#> # … with 6 more variables: instrumentalness <dbl>, liveness <dbl>,

#> # valence <dbl>, tempo <dbl>, duration_ms <int>, time_signature <int>

You can do anything you want with this information, though it’s helpful to be versed in either sound engineering and/or music theory to truly get the most of this.

For example, I might be at that lonely intersection of “loves progressive rock, especially Rush and vintage Genesis” and “also loves classic four-on-the-floor disco that I know RuPaul also loves.” A 4/4 time signature is called “common time” for a reason and it’s alien to think of many danceable pop songs that are in something other than 4/4, though MGMT’s “Electric Feel” (6/4) and Outkast’s “Hey Ya!” come to mind.1

Let’s see if there’s any RuPaul songs that feature an irregular time signature.

rupaul_features %>%

count(time_signature)

#> # A tibble: 1 × 2

#> time_signature n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 4 13

…Nope. No one will confuse “Sissy That Walk” with “Dance on a Volcano” or “Tom Sawyer.” You typically write songs you want to dance to in 4/4, or 3/4 (if you’re feeling fancy). You write songs to evoke discomfort in something else. Apologies to Jimmy Pesto Jr., but 7/8 and not 9/8 is the real “dance kryptonite.”2

Here’s a feature of Spotify that I find fascinating. get_track_audio_features() returns Spotify’s algorithmic assessment of the key in which the song is. It’s returned as an integer, which is matched to standard pitch class notation where C is 0, C♯/D♭ is 1, D is 2, and so on until arriving at B (11). To match this integer to something more intuitive for the musically inclined, I’ll create a quick scale here and merge it into the data, performing a group-by count to see what emerges as RuPaul’s preferred pitch.

tibble(key = c(0:11),

pitch_class = c("C", "C♯/D♭", "D", "D♯/E♭",

"E", "F", "F♯/G♭", "G",

"G♯/A♭", "A", "A♯/B♭", "B")) %>%

left_join(rupaul_features, .) %>%

group_by(pitch_class) %>% count()

#> # A tibble: 8 × 2

#> # Groups: pitch_class [8]

#> pitch_class n

#> <chr> <int>

#> 1 A 1

#> 2 B 1

#> 3 C 1

#> 4 C♯/D♭ 2

#> 5 D 1

#> 6 E 1

#> 7 F♯/G♭ 4

#> 8 G 2

According to Spotify, RuPaul is partial to featuring her songs that are in the key of F♯.

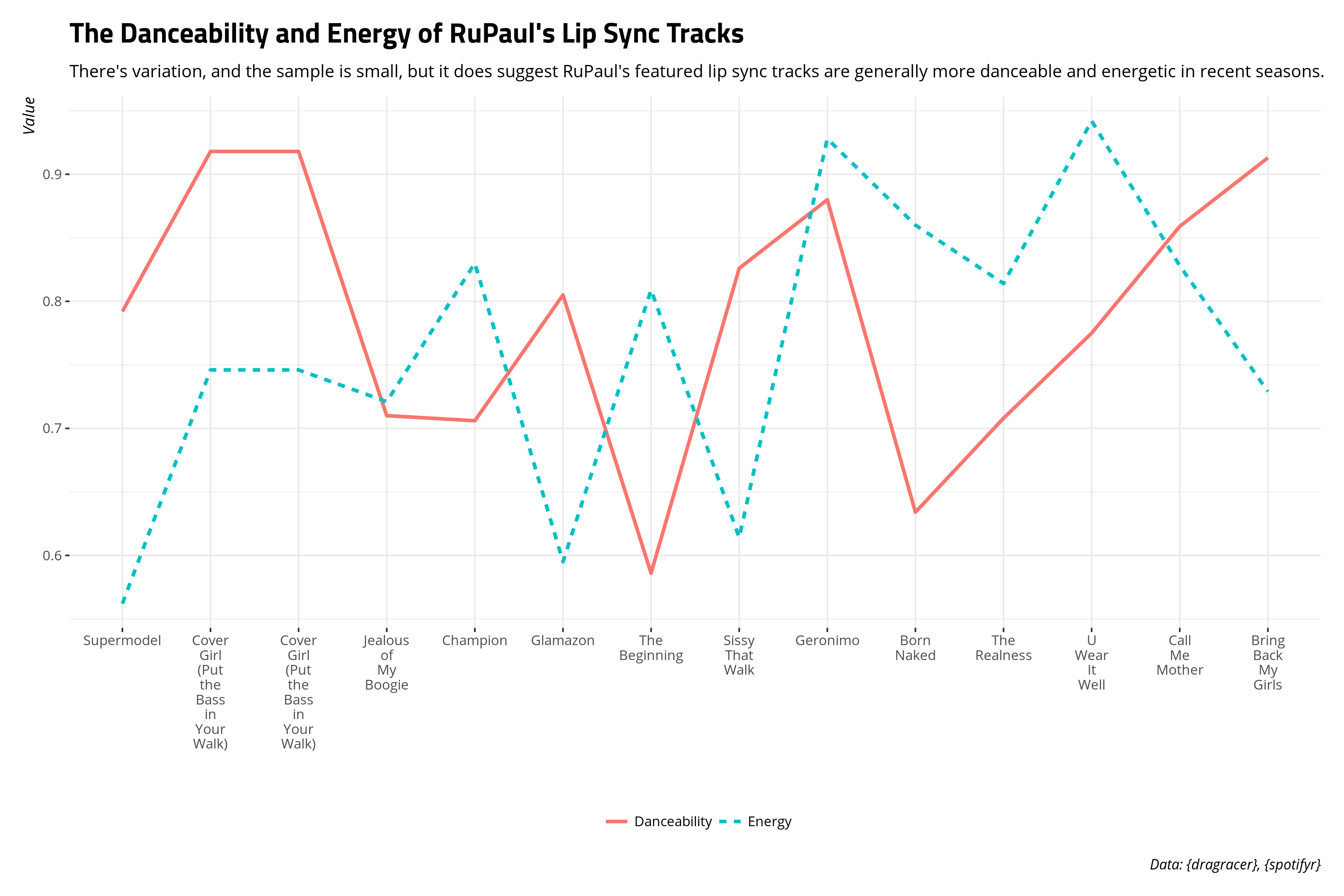

You could also use these data to explore potential trends and changes in RuPaul’s selected catalog over time. For example, are RuPaul’s tracks getting progressively more energetic and danceable? That was a hunch I had based on her more recent songs compared to, arguably, her signature song (“Supermodel”). You’d have to build in an assumption—justifiable in this context—that new RuPaul songs that appear on her show are indeed newer tracks. It’s why “Supermodel” (released in 1993) features on the first season of the show and successive songs are new tracks strategically timed with the release and production of a new season of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

You can get that information from the danceability and energy columns returned by get_track_audio_features(). Both are determined algorithmically by Spotify, based on an audio analysis of the song. “Danceability”, the conceptual definition of which should seem straightforward, is determined by tempo, rhythmic stability, beat strength, and overall regularity. “Energy” is a measure of intensity and activity of the song. Both are standardized to be between 0 and 1 with higher values indicating more danceability and energy.

The following graph suggests the lip sync songs that RuPaul selects from her growing catalog have generally become more danceable and energetic over time.

addline <- function(x,...){

gsub('\\s','\n',x)

}

rupaul_songs %>%

left_join(., rupaul_features %>% select(id, danceability, energy), by = c("spotify_id"="id")) %>%

mutate(season_episode = paste0(season,"e",str_pad(episode, 2, pad="0"))) %>%

select(song, season_episode, danceability, energy) %>%

gather(var, val, -season_episode, -song) %>%

mutate(var = str_to_title(var)) %>%

ggplot(.,aes(season_episode, val, group = var, color = var, linetype=var)) +

geom_line(size = 1.1) +

theme_steve_web() +

scale_x_discrete(labels = addline(rupaul_songs$song)) +

labs(linetype = "", color = "", x = "", y = "Value",

title = "The Danceability and Energy of RuPaul's Lip Sync Tracks",

subtitle = "There's variation, and the sample is small, but it does suggest RuPaul's featured lip sync tracks are generally more danceable and energetic in recent seasons.",

caption = "Data: {dragracer}, {spotifyr}")

This is a work in progress, and I offer it here to at least put something on my blog after all this time. I also offer it as a potential project if someone wants to help me flesh this out for the full catalog of lip sync songs that have appeared on the show. Right now, I can’t credibly commit time to expanding this data set given all sorts of other things on my plate. However, it’ll eventually get done for all songs that have appeared on RuPaul’s Drag Race as lip sync songs. This partial analysis points to the data’s potential use.

-

There’s an interesting academic discussion about how you should count “Hey Ya!”, at least as far as I understand it. As a whole, it might be understood as a 22/4 time signature though, practically, you can think of it as five bars of 4/4 with a 2/4 hiccup after the third bar. I suppose you could say something similar about “Electric Feel”, which could be understood as a 4/4 with a 2/4 add-on. However, I think 6/4 best captures the phrasing of the song. I hear the song as wanting to land on the 6 and not the 4. ↩

-

I wish I knew where to source this, but I recall watching an interview with either Neil Peart or Geddy Lee who advised fans who wanted to dance to “Tom Sawyer” to not do that because, and I quote, “you’ll hurt yourself.” ↩

Disqus is great for comments/feedback but I had no idea it came with these gaudy ads.